We’ve all been there: staring at a blank document, scrolling on TikTok, or suddenly deciding to reorganize our entire room rather than beginning the task we know we should be doing. Procrastination is more than just a bad habit or a problem with time management. It's often entangled in emotions, self-doubt, and mental overload for me—and most likely for you as well. Despite being one of the most common challenges we encounter, it is frequently misunderstood. Understanding why we procrastinate is the first step toward increasing our productivity.

The Emotional Element of Procrastination

Procrastination isn’t always about delaying tasks, it can also be about avoiding discomfort. When we procrastinate, what we're often really trying to avoid isn't the task but rather the negative emotions the task arouses, whether those emotions are fear of failure, anxiety, self-doubt, or even boredom. Avoiding these negative emotions is central to what researchers have described as "task aversion," where we delay starting because the task is somehow psychologically threatening (Sirois & Pychyl, 2013).

For example, a student might delay starting a term paper not because they lack the skills, but because the assignment triggers fears about their academic abilities or worries about disappointing others. Similarly, someone looking for a job may delay their application because they fear rejection or feel overwhelmed by self-doubt.

The Neuroscience of Delay

Limbic System: This part of the brain is associated with emotions, motivation, and reward processing. It's highly sensitive to immediate pleasure and can easily override rational thought when seeking instant gratification (Heatherton, 2011).

Prefrontal Cortex: This region is responsible for higher-level cognitive functions like planning, decision-making, and controlling impulses. It helps us weigh the long-term consequences of our actions and resist the urge for instant gratification (Friedman, 2022).

Procrastination, according to neuroscience, occurs as an ongoing struggle between the emotional center of the brain (the limbic system) and the rational center (the prefrontal cortex). Because the limbic system is motivated by instant gratification and enjoyment, it makes us desire more immediate rewards like scrolling through social media than delayed rewards like finishing a paper.

This can explain why procrastination can feel irrational. You know you have to do the work and you may even want to, but your brain is wired to seek short-term comfort over long-term success, especially when emotions are running high.

Time Inconsistency and Temporal Discounting

This ties into an important concept in procrastination research called time inconsistency. This is the tendency of our brains to place value on immediate rewards more than future ones (Buffone, 2021). This is why the appeal of binge-watching a TV show right now outweighs the satisfaction of finishing an assignment not due for another week.

This phenomenon is also linked to temporal discounting, where we discount the value of future outcomes (Zhang, 2024). So even though we know completing a task will bring relief, pride, or progress toward a goal, our brain undervalues that reward if it feels too far away.

The Role of Perfectionism and Fear

Perfectionism can also play a role in procrastination. People who are worried about making mistakes may delay starting tasks in order to avoid the discomfort of imperfection. This fear can be particularly overwhelming, especially for students and high achievers (Sederlund, 2020).

On the other hand, procrastination can also serve as a self-protective mechanism. If you wait until the last minute and don’t do your best, you can attribute any failure to a lack of time rather than a lack of ability. It’s a way of preserving self-worth, but at a high cost.

The Connection Between Mental Health and Procrastination

Because our ability to make decisions is closely tied to our emotional and mental state, a person’s current mental health can significantly influence whether they feel capable of beginning a task. As research suggests, procrastination is often used as a coping mechanism for emotional strain or mental fatigue.

Anxiety, Depression, and Procrastination

Both anxiety and depression can interfere with decision-making by altering how the brain evaluates risk, reward, and the effort required for a task. People with anxiety are more likely to overestimate potential risks, especially when specific fears are involved (Bishop, 2018). For example, someone with social anxiety who needs to prepare for a presentation may find the situation highly threatening, to the point where they delay or avoid the task completely. In contrast, depression tends to reduce energy, motivation, and the anticipation of reward, which can make even small tasks feel overwhelming and pointless (Bishop, 2018). Because both conditions can distort how we judge effort and outcomes, avoiding a task, through procrastination, often feels like a protective response to being emotionally uncomfortable.

Breaking the Cycle: Evidence-Based Strategies

The good news? Procrastination is a habit, and like any habit, it can be changed. Here are some strategies backed by psychology:

1. The Pomodoro Technique

This technique was created by Francesco Cirillo (1999), and involves working in a 25-minute focused interval followed by a 5-minute break. It is used to reduce mental fatigue and keep motivation high.

2. Implementation Intentions

These are specific, “if-then” plans that prime your brain for action. For example: “If it’s 9 a.m., then I will write one page of my report.” Research shows that these intentions increase follow-through and reduce avoidance (Gollwitzer, 1999).

3. Time Blocking and Scheduling

Rather than relying that you will feel motivated, schedule tasks into your calendar. Studies suggest that planning when and where to complete a task increases completion rates (Wertenbroch, 2002).

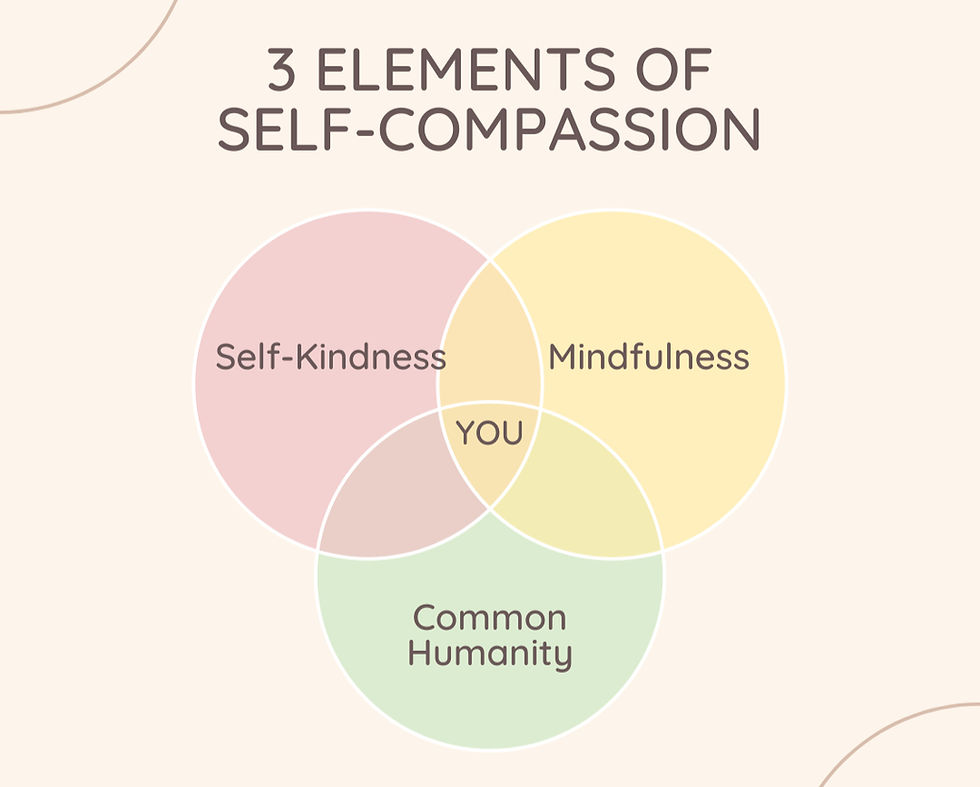

4. Self-Compassion Over Self-Criticism

Research shows that self-compassion, not self-punishment, is linked to higher motivation and less procrastination. Being kind to yourself reduces emotional avoidance and fosters resilience (Neff, 2003).

Final Thoughts

Procrastination is not simply a personal shortcoming—it serves as a psychological signal. It tells us something important about our emotional needs, our beliefs about competence, and our relationships with time. Productivity isn’t just about doing more, it’s about doing what matters with clarity and care.

By understanding the psychological roots of procrastination, we can approach our goals with insight and intention. And sometimes, the most productive thing we can do is pause, reflect, and start one small step at a time.

References

Friedman NP, Robbins TW. The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022 Jan;47(1):72-89. doi: 10.1038/s41386-021-01132-0.

Sirois, F. M., & Pychyl, T. A. (2013). Procrastination and the priority of short‑term mood regulation: Consequences for future self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(2), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12011

Wertenbroch, Klaus. (2002). Procrastination, Deadlines, and Performance: Self-Control by Precommitment. Psychological science. 13. 219-24. 10.1111/1467-9280.00441.

Zhang, P. Y., & Ma, W. J. (2024). Temporal discounting predicts procrastination in the real world. Scientific reports, 14(1), 14642.

P. Sederlund, A., R. Burns, L., & Rogers, W. (2020). Multidimensional Models of Perfectionism and Procrastination: Seeking Determinants of Both. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 5099. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145099

.png)

Great read!